Lists vs. Fractals

TLDR: I have a hypothesis that problems in programming often have fractal-like nature. This causes delays in work and makes the management of tasks more complicated. Our task-management tools cannot properly handle fractal tasks because they are based on the linear concept and treat task dependencies as a second-class citizen. If we take into account the fractal nature of tasks, such management may become easier.

I also propose an example of tool for such kind of task management. You may take a look at it, but it’s not obligatory.

Welcome to the fractal trap!

Let’s explore an imaginary (but quite typical) situation. Say you have a “software project”:

- a big pile of code,

- and some kind of “task tracker” used to plan a work upon this code.

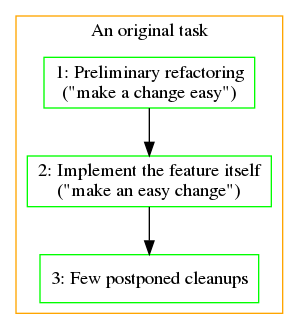

At the beginning of a new week, you choose a single “task” from this tracker and start to work on it. This task has already been “estimated” and split into a simple, straightforward-looking checklist.

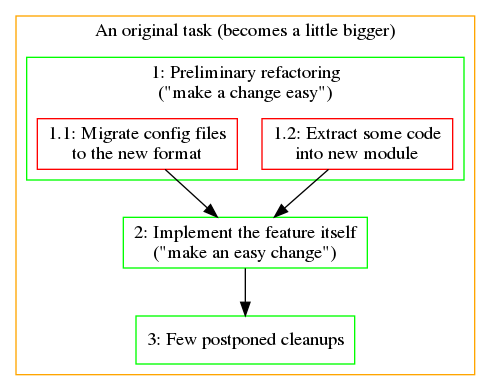

Then you simply start moving through this list. At the first glance, these steps appear to be simple, but when you dig into the first one, it suddenly grows in size.

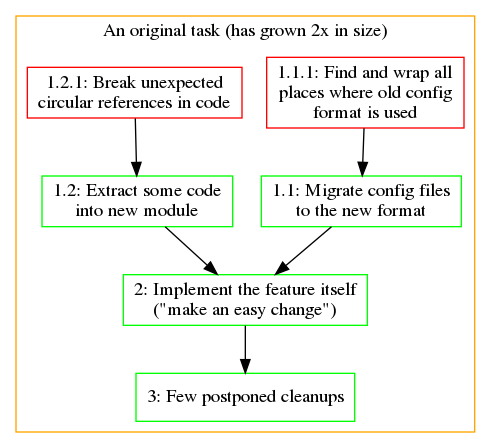

There might be a blocker or significant subtask for almost every simple step in your software project. Your “first subtask” grows more and more, becoming comparable in size to the whole original task.

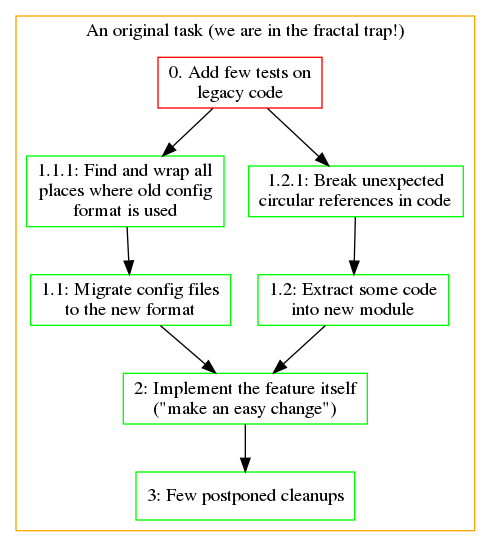

Finally, you’ve found that your code to be changed is not covered with tests. Much bad, need to fix it!

Of course, this isn’t a rant against refactoring or tests! They are truly needed, especially in complex and aged code bases. I rant against the way we’ve used to deal with tasks.

Sierpiński triangle, image from Wikipedia

Like a fractal, a software development task could easily hide other subtasks with comparable size and/or complexity. They could be invisible to you until you face them. That’s why I call this “a trap”. Fractal traps usually come from different sources: code coupling, leaky abstractions, requirements shift, and so on. They are almost unavoidable. I think it wouldn’t be wrong to claim that most developers have to deal with them at least sometimes.

But how do we usually deal with such a kind of problem?

A classical approach

The most naive approach to handling this problem is simply ignorance. Is each task growing in size? OK, let’s deal with it. Just keep going until the final goal is achieved.

Alas, by keeping all substeps in the same task we make them quite opaque. Something is happening in the task, and it will be finished someday.

Depending on your working environment and team agreements, this situation could or could not harm your performance. In most cases, I’m afraid, it does. There are thousands of words written that could explain better than me why large tasks decrease your productivity.

Of course, this is a common problem, and there is a solution already! Let’s proceed to it.

Divide and conquer

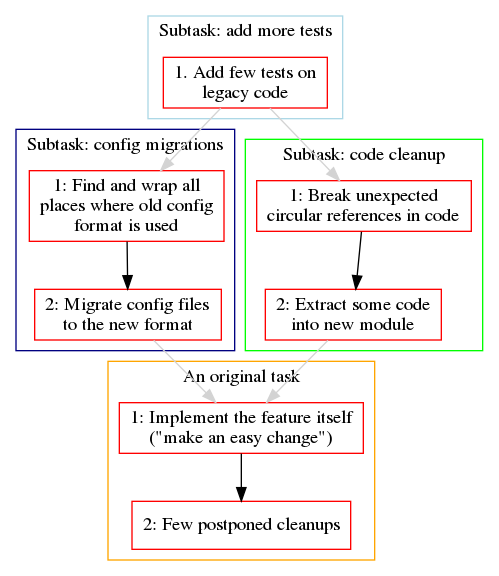

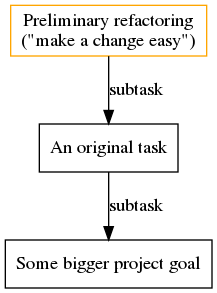

Once you get tired of big tasks, you start splitting them into smaller pieces. In your new working process, each subtask is only allowed to become a full-fledged task in your tracker once you notice that it’s big enough. Like this:

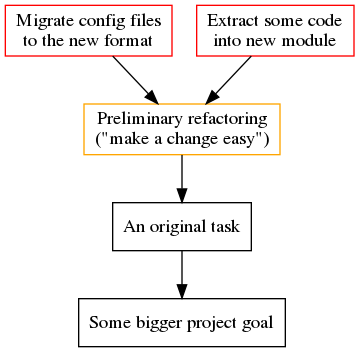

Oh, wait!.. Much more often you’ll see it like this:

Ticket Label Assignee

---- ---- ----

#321 An original task You

#322 Config migrations You

#323 Code cleanup You

#324 Add more tests You

When splitting your task into subtasks, you usually have to pay a new tax: the tax of manual dependency management. Starting from now, your every decision about what subtask to take next gains an additional cost. When you ask a question about relations between tasks, you have to visit one or several of them to find an answer:

-

Is there anything that prevents us from starting work on task #N? Well, dig into it and check whether there is any “blocker task” on the card.

-

Which tasks have no blockers? Visit all of them and take a look.

-

Which task has the highest priority? Use priorities you’ve assigned to them manually. Of course, you should better ignore the fact that your “super-duper critical” task could easily be blocked by another task that looks like “senseless crap” in isolation.

Is it possible to reduce this tax? Let me introduce a possible way to do it.

Respect the structure

Because of the task-oriented nature of most task-tracking tools, the relations between these tasks are second-class citizens. How could you ever spot the fractal structure when the only thing you get is a big unstructured pile of tickets? To make this happen, we should try to visualize this tree and introduce our dependencies as first-class citizens. But I believe that we deserve to have good task-management tools that could help us to handle with complex and tangled nature of software development.

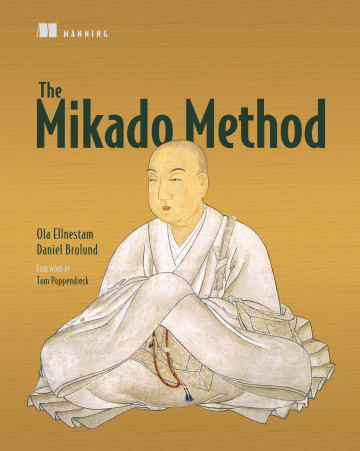

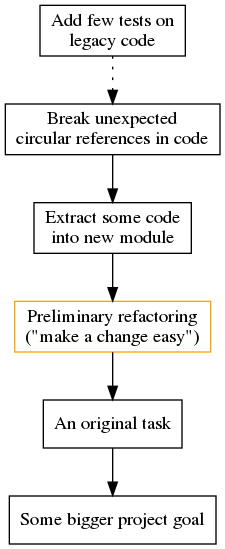

How could a task workflow look like in such a tool? This vision is primarily inspired by ideas taken from a brilliant “The Mikado Method” book by Ola Ellnestam and Daniel Brolund.

At the beginning of a new day, you choose a single goal from this tracker and start to work on it. Several days ago you’ve already thought about this goal and preliminarily split it into three subtasks.

The tool highlights non-blocked tasks for you making them easier to spot. So you simply choose to start from the first one. To improve your focus, you hide other subtasks - they are not needed at the moment.

At the first glance, this step appears to be simple, but when you dig into it, it grows in size. You reflect these changes in your tracker by adding new subtasks. In your task tracker, it’s a quick and easy operation.

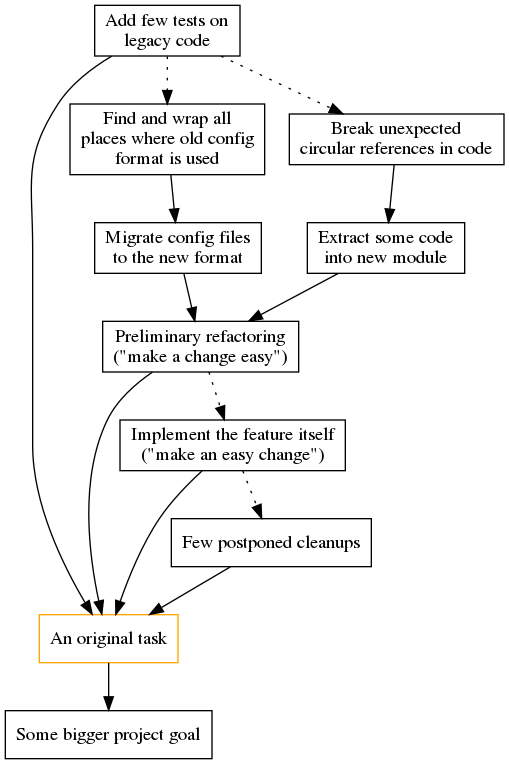

A count of subtasks still grow, but you’re prepared for that. No matter how deep you dig in, your tool always allows you to control the complexity of your current working context. You could split your tasks into parts to focus on a single chosen part. You could draw relations between subtasks to provide an order of execution. You could remove these relations when you see that two tasks do not depend on each other. All these operations allow you to keep the number of your next actions small.

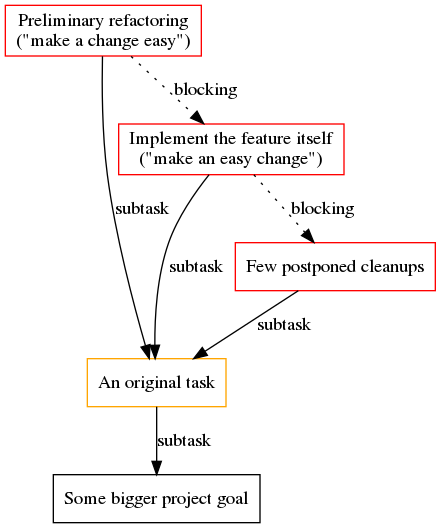

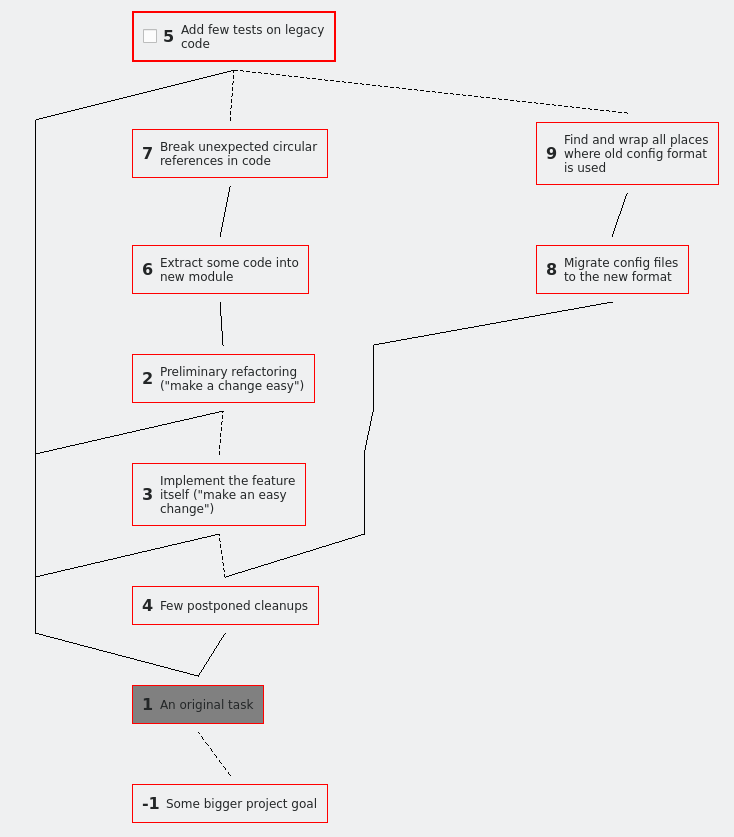

From time to time you may switch from “working mode” into “planning mode”. Instead of “zooming in” into a single subtask, the tool lets you “zoom out” to see a whole picture. It may look like this, for example:

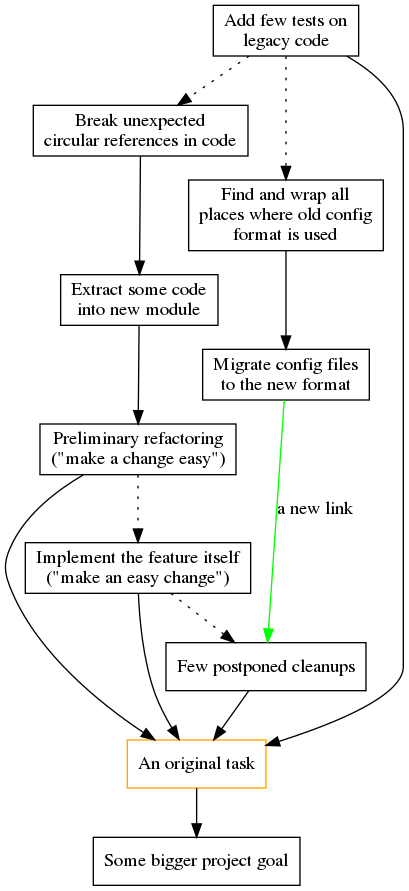

Now let’s imagine that you decide that one of your refactorings could be performed later since it doesn’t actually block your work. The only thing you need to do is to insert a new subgoal between an original task and this refactoring.

Then let’s zoom into the “Preliminary refactoring” again. It’s become simpler than before because the “Migrate config files” subtask doesn’t block it anymore.

You may simply take the topmost subtask and solve it. After you’ve ordered your small steps, all of them could be taken one after one.

Is it better?

This process may look scary when you’re unfamiliar with such kind of task management. At first glance things seem worse: not only have more subtasks to manage right now, but also many more explicit dependencies between them. The total amount of “items” has been increased compared to previous approaches.

But when you look at how does it behave in dynamics, things do change. With such a tool, you could easily change the scale of thinking and planning.

In the “global view” mode, you usually don’t work on any single task. Instead, you look at relations between tasks, reorganize them, spot patterns, and think about the big picture. It’s very similar to the “mind mapping” technique which is used to organize connections between ideas. You only need to decide what is relatively more important, and what is relatively less important. The tool takes responsibility for the absolute ordering. Every line in this graph becomes the record of your decision. And after returning to the “close view” mode, you don’t need to keep these decisions in your mind.

The only thing you need to focus on is how to finish a simple “top” subtask. When it’s done, another subtask will become unblocked. This allows new tasks to become “top” ones. This process strictly follows the order you’ve defined earlier. Now your task tracker works not like mind mapping but like a TODO-list. But it’s still the same tool!

Does it have drawbacks?

Of course, there are several issues.

Tree trimming takes time. Almost obviously, when you manage many small pieces of your task and relations between them, it requires a larger part of your time. On the flip side, detailed and flexible planning often allows one to foresee and avoid traps before falling into them.

And it saves the time you might lose when escaping from these traps.

It requires skill. Here’s a less obvious but more important point. Without experience in decomposition, you often don’t know how to split your tasks properly. But to gain experience, you need to do it regularly. Even after ~5 years of using my tool I still find new ideas to improve my techniques. As an example, I still don’t know how to work with structureless tasks like writing big pieces of text (especially this one).

Risk of context loss.

Alas, this happens regularly.

Say you have two big subtasks of your current task (A and B).

Each one has several nested subgoals (A.1, A.2, A.3, B.1, B.2, and so on).

While working on subtask A you notice that A.2 is a prerequisite for B.1 and place a dependency between them.

After some time you switch from A to B and A.2 (a blocker for B.1) suddenly becomes unclear for you.

Because it’s described in several simple words like “Do X” which are clear in the context of A but not in the context of B.

Solution?

You need to always keep some additional context together with a single subtask.

Observability issues. Also pretty obvious: when you have a lot of small subtasks, at some moment they become difficult to find.

Risk of task duplication. As a consequence of the two previous issues, duplicated subtasks appear periodically. On the other hand, this could happen to any task tracker, right?

All of these issues could be mitigated with a good tool. Here we go to the last drawback!

Lack of good tools. I’ve looked at tens of the most popular task management tools, and none of them is close enough to the described functionality. I’ve even had to create one by myself. It allows for understanding the concepts described here but still lacks a lot of important features. But if you only need to evaluate the ideas I’ve described here, it may help you.

The same diagram as above, implemented in SiebenApp

The same diagram as above, implemented in SiebenApp

UPD (2022-03-18): Here I’ve found a reference to a similar MacOSX tool TaskHeat. But I’m a Linux-boy without MacOS, so I couldn’t check it by myself. This is an excercise left to a reader.

Is it Gantt diagram?

The one who has enough experience in development may feel suspicious after my claim: “we have lack of tools”. Of course, there is a whole class of tools for “management of tasks and dependencies” we have to live with for decades.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

Often, it’s too far from a symbiosis. The following short story perfectly illustrates the problem:

When I first started contracting in London, I worked as the only developer on a team that had TWO project managers - one in Leeds and one in Swindon. Every week I dropped working software, they tested it, and the plan changed.

— Jason Gorman (only, more indoors than usual) (@jasongorman) August 17, 2021

Every Friday I had to travel up to Leeds and then down to Swindon to help them update their project plan. That was a day out of every week for 3 people to change a Gantt chart that was out of date by the following Tuesday.

— Jason Gorman (only, more indoors than usual) (@jasongorman) August 17, 2021

I've believed ever since that detailed long-term planning in s/w is a waste of time. If you iterate working software fast enough, you can deal in reality, not guesswork.

— Jason Gorman (only, more indoors than usual) (@jasongorman) August 17, 2021

And, yes, that means they spent 20% of their entire development budget (i.e., me) maintaining a Gantt chart.

— Jason Gorman (only, more indoors than usual) (@jasongorman) August 17, 2021

I have to draw a line between the two approaches. Why do I distinguish a “fractal-oriented” approach from the well-known Gantt-chart approach? I’d like to point on the following difference. Gantt tools are oriented towards managers, not programmers. They’re mostly focused on very different things (duration, “resources”, “materials”, large scope) and provide a relatively heavyweight workflow.

Things should change when a planning tool lies in the hands of perfomer. When it doesn’t have any distracting or heavyweight concepts. When it could simply be used in parallel with the work itself without interrupting the flow. Then complex problems would become much easier to solve.

Yet at this point, I still have more questions than answers. How many programmers actually face such kinds of issues (and how often)? Did I overcomplicate it? Wouldn’t my remedy be worse than the original disease?

Let’s leave them open for now.

Acknowledges

This article wouldn’t exist without the influence of the following people:

- Jessica Kerr in her “Code is a coastline” have inspired me to write my own thoughts about the fractal nature of software tasks. It’s only my fault that it took several months to formulate an answer!

- Ola Ellnestam and Daniel Brolund with their “The Mikado Method” book have changed my way of thinking about tasks. After several years of practicing, I find it way more natural, easy and practical than the classical big-ticket-oriented approach.

- Sergey Tselovalnikov, my Russian ex-colleague, gave me much enough courage to start writing in English. He has also given many useful comments on the draft version of this essay. Please check out his blog.

Additional links

In case you want to take a look at the herd of task trackers, take a look here or here.

Mr. Michael “GeePaw” Hill has also posted interesting thoughts on similar topic here and here.

Comments

Sorry, comments are currently disabled here. Once I’ve tried to use Disqus, but it was a kind of mess that I don’t want to be repeated.

But any kind of feedback is highly appreciated! Please leave your comments under the following tweet:

New blog: Lists vs Fractals https://t.co/xt2IsC8YLE

— Andrey Hitrin (@ahitrin) November 24, 2021

List-based task-management tools and thinking vs the Fractal nature of programming tasks