A model of small decisions

Would you like to walk here at night? Photo: Andrey Hitrin

Would you like to walk here at night? Photo: Andrey Hitrin

Sometimes thoughts of our human nature makes me sad. Our attempts to share own thoughts to others can be compared with attempts to find a way out from the dense forest during a moonless night aimed only with a laser pointer. The only thing you could show to others is a little spot of light randomly jumping back and forth, appearing and disappearing spontaneously. How could you find a trail with such a weak tool? How could you convince your party to follow it? How could you understand if this trail should take you out of the forest?

That’s why people try to invent new and new words to explain same conceptions. Everyone hopes that his/her explanations will be good enough to make other understand “the inner nature of things”. Most of the time it’s worthless: others don’t see more than chaotically jumping light spot.

Nevertheless, here is my own attempt. Words written here are not the truth, they are nothing more than my biased reflection of it, based on my limited experience. I don’t know if they are contains some wisdom, or just a bunch of useless commonplace. That’s you who will judge.

The quest for mastery

As usual, I want to speak about programming.

There is an idea that programming has many similarities with martial arts or musical performing. In all of these areas you could show some results after relatively little amount of practice, but it requires years of studying and training if you want to achieve truly significant level. Often you even have to perform at the edge of your own abilities.

And when you want to perform at such level, you must be aware of all aspects of your profession. Today I want to speak about small and often invisible decisions that guide you through your everyday work.

Small decisions

In our job, you need to do a lot of small decisions every day. Just watch after yourself during work process, and soon you will be able to notice them.

Imagine you’ve just started to work on some feature. Small decisions appear instantly. How will you start you work? By reading documentation, or by checking code out, or by asking your colleagues? Change some code first, or think about test cases? Implement straightforward change, or roll out few refactorings beforehand?

How will you deal with “bad code” challenging your way: ignore it, or try to fix right now, or defer a fix for a “better time”? How will you act when feeling struck: ask your teammate (and which one, when you have several of them), google your problem, stackoverflow it? Or maybe simply wait until an answer forms inside your head (also known as ‘procrastinating’)? Or maybe wait until someone asks you about the progress?

That’s what I mean by the “small decisions” term. A lot (tens, or even hundreds per day) micro-choices you make in your work. Sometimes you make this choice consciously, but often not! You choose your path without even thinking about it, without even noticing the fact of choosing.

Does this matter? I think it does.

Choose/move dichotomy

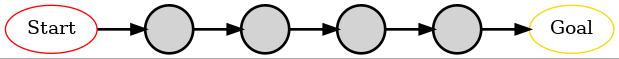

Let’s draw your way through the imaginary “work task”. I like to draw graphs, so it’s depicted as a graph.

Every node here is a small choice you’ve made. Arrows represent the “movement” between them. A number of intermediate steps is arbitrary and depends on your own definition of “small decision”. When you zoom out, they almost disappear. When you zoom in, a single decision could be even as small as “which finger should hit the given keyboard button?”. Here I choose something intermediate.

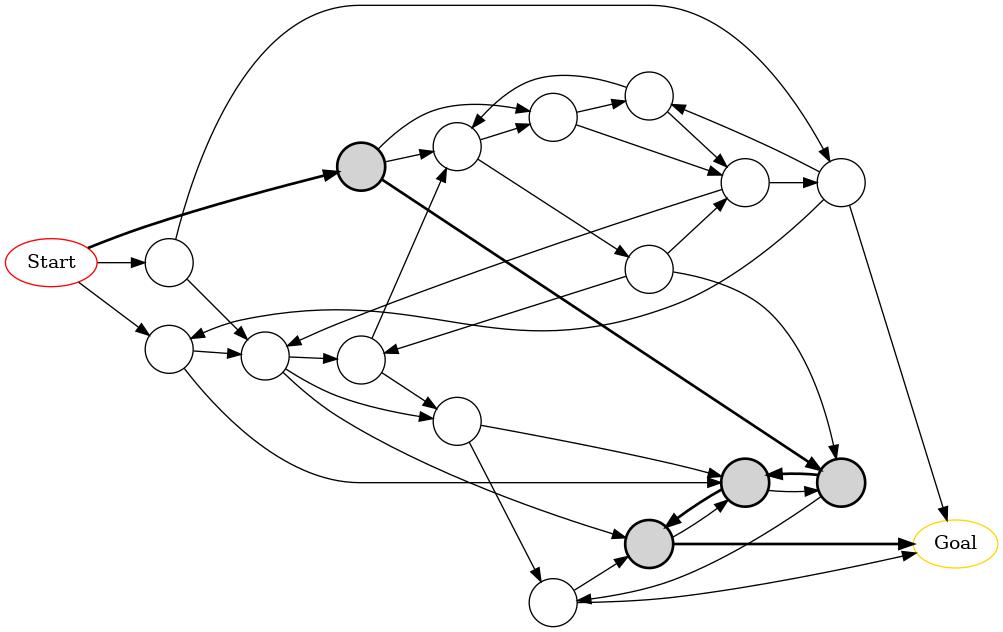

And now let’s imagine more possible moves that also could solve your task.

Here we see a whole net of possible decisions. What would happen if you choose another step at the start? Some of alternative ways could be shorter (containing less hops), some of them could be much, much longer! Of course, here I simplify the problem a lot. But I need this simplification to show you few important things. Here are following key points:

-

You have to make a lot of decisions. There are points in almost every task that requires your decision. For example, you need to ask yourself at least once: “have I reached my goal?”. And then either get done with it or continue to work.

-

Even small decisions may have big impact. When you choose the wrong path at start, it may lead you far away from the goal. You have to move along the non-optimal path or return back to the start.

-

Every decision takes your time and energy. Usually delay on decision come from one of two or three sources. The first source is delay between a question and an answer. Say you’re struck and don’t know where to move next. You try to ask your colleague via IM for help. But currently he/she is busy, and only can answer you in 20 minutes. This delay is the cost of your decision. The second source is delay on choosing by itself. It may happen when you see two or more alternative paths and hesitate which one should be followed on (maybe a “frustration” word is suitable here). The third one is a need to remember a known, but currently forgotten solution (more on this in the next chapter).

All of these make me conclude that it’s important to consider the impact of decision making to our work. Low-quality decisions reduce your productivity every day. They make you stray in the dark without help.

Surprisingly, even after reading a lot of books and articles on programmer’s productivity, I haven’t found enough much attention to this theme (please correct me if I’m wrong!). That’s the main reason why I’ve started to write this article.

A table of decision rules

OK, maybe quality of decisions is important. But how could we ever manage them? Here I suggest a simple model. As any other model, it doesn’t describe things as they are, but uses simpler (and more manageable) view on it instead. The main power of modeling is its ability to predict effects of our actions, but we should never forget about its boundaries. Outside boundaries, our model will be wrong - and I don’t know where they are. I sincerely hope that your feedback could help determine them.

The model is heavily inspired by the work [1]. Think for a minute: this paper is already 40 years old! Why no one still haven’t developed it into the similar direction as I did? I don’t know (or maybe I’m just wrong - please let me know in that case).

This prelude was necessary - but now let’s proceed to the model. So, suppose each of us have some kind of table in the head (I warned you, it’s a simplified view). It contains two columns:

-

Trigger. An external stimulus that could activate current “table row” or rule. For example: a piece of code you’re looking at; a letter from CI server; a message from your colleague; your current thoughts about your task; and so on.

-

Acton. A thing you do when the rule is being activated.

It may look like this:

| Trigger | Action | |

|---|---|---|

| You need to find the source of a bug | → | Run git bisect to find a commit where it was introduced. Then analyse the code |

| You want to check if your code is ready to deploy | → | Push changes to remote repository and run CI service |

| You want to check if your code is ready to deploy | → | Push changes to remote repository and ask someone to review it |

| You have detected the "smell of ugly code" | → | Try to refactor it out immediately |

| You have detected the "smell of ugly code" | → | Ignore it: we don't have time to refactor |

| Selenium test on CI server has failed | → | Look at screenshot to check where is the problem |

| Selenium test on CI server has failed | → | Look at job logs |

| Selenium test on Ci server has failed | → | Launch that job again: maybe it's just flaky test? |

| You're struck and don't know what to do next | → | Ask your teammates for help |

| You're struck and don't know what to do next | → | Wait until someone asks you what's going on |

| ... | → | ... |

This table has important properties:

-

It changes over time, depending on your own experience and knowledge. When you discover new tricks, they have a chance to hold in the table. In other hand, even the best practices without repetition pass away from your memory. Of course, they do not always being erased completely. Rather, they are removed from “the cache”, the fastest part of your memory. And you’ll have to make an effort of remembering to bring it back.

-

It has limited size. You cannot know literally everything. You cannot have the best solution for every possible situation you may face.

-

It may have several rules for one situation. In that case your final choice may depend on current context. Sometimes you may even need to spend additional time and effort to make a choice between alternative actions (“resolve a conflict”).

-

It models only small decisions. Only little choices that often even pass your spotlight and perform automatically could be modelled that way. In terms of “Thinking, Fast and Slow” [2], it relies to the “System 1” only.

There could be different sources where these rules come from:

- Your previous successful and unsuccessful experience.

- Observations of your teammates: how do they behave in different situations.

- Direct rules of the project you’re working on (like “use

./gradlew checkto verify correctness of your code”).

I hope to write more on it in following articles, but the current one has grown big enough. Seems like I have to go to conclusions.

Any benefits?

What benefits could the awareness about these rules bring to you?

First of all, you should take into consideration the limited size of your memory. In order to make better decisions, you need to consciously “tune” your rule table. How could it be done?

-

Remember your good (effective) decision rules. Practice them from time to time so they don’t leave your working memory. Write them down in known place so they could be remembered effectively when needed.

-

Try to free your memory from unneeded decision rules. If they aren’t needed, forget them. If they still may be useful, keep them in an external place. For example, imagine you have a complex task management ceremony consisted of 7-8 steps that needs to be performed once a week. You should not try to keep this ceremony in your memory. Writing it in a form of simple instruction or checklist is much better. Now, you need to remember the only one thing: a place where your checklist lies.

-

Try to avoid multitasking. Different tasks require different decision rules. When you switch back and forth from one task to another, these rules fight for a place in your working memory. There is no guarantee they all could fit inside altogether. It’s highly likely they couldn’t.

-

Review your working habits regularly. Are they effective enough? Have some of them become obsolete? Circumstances change over time, and your habits that were effective a year or two ago, now could pull your performance down.

-

Check out how much time to you spend on conflict resolving between several possible actions. Try to extract strict and distinct rules which action in which case you should prefer. This should decrease your waste of time and energy the next time you face similar dilemma.

And, if we back for a while to the first part of the model (“choose/move”):

-

Try to minimize amount of decisions you need to take during one task. Split big tasks into smaller and well defined steps, so you need to make few small decisions between them. Remove obstacles that pulls you or your teammates away from the streamline (dirty code, small but noisy bugs and so on).

-

Increase speed of your tools. The faster they give feedback, the less time you waste on waiting.

-

Remember: there is another way almost everywhere. When you feel struck and cannot see any good next move toward your goal, think for a while. Maybe there is a way for you, but your thought patterns prevent you to spot it?

An important role both in professional music and in martial arts plays the concept of “minimizing waste of energy”. Fingers of a guitar master don’t flicker spontaneously, they are fully controlled. A kung fu master doesn’t hit randomly. Neither should you.

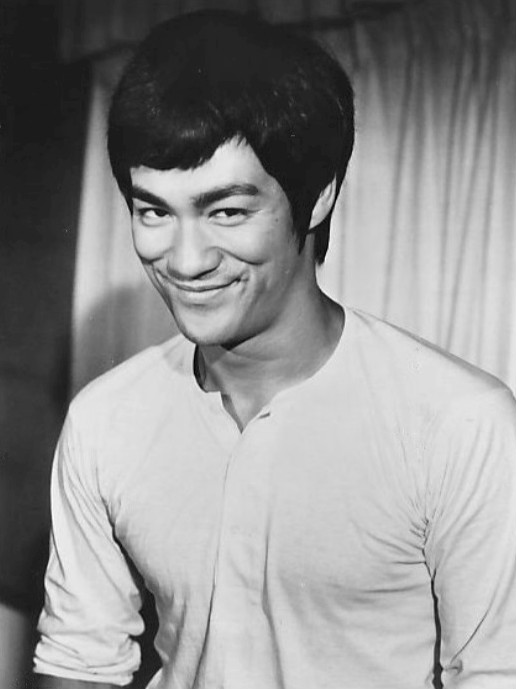

Look at the real master of small decisions!

Bruce Lee. Image from Wikipedia

Watch after his movements from tournament records. He seems to move slow and even lazy, but no one can beat him - because he performs no excess movement, no excess small decision.

The final words

For me, the described model have become surprisingly fruitful. It very well “describes” many effects and problems observed in the IT field. I’m curious why does it happen: either because it’s really good and predictive or because it’s way too fuzzy and allows to gain any answer you want (e.g. it’s actually useless). That’s why I want to provide it onto your court.

What I’d like to cover next:

- Gaining and losing experience. Is it always good to know a lot?

- Empathy. How could this model help you understand others’ behavior and improve communication?

- Team performance. So called “10x programmers”, pair and mob programming, an effect of diversity.

- Clean code, dirty code, legacy code. How to deal with entropy.

- Maybe something more…

If you like, try to apply the model to given themes for yourself. Will our conclusions match?

I will be very glad to receive your feedback on this topic! Is this model useful for you? Does it provide wrong results? Is this article way too abstract? Is it filled with obvious things?

Comments on this blog are not available yet (sorry!), so I’d like to ask you leave comments under the following tweet:

My new blog on programmer productivity: "A model of small decisions" https://t.co/Pq5ErHztk6

— Andrey Hitrin (@ahitrin) November 3, 2020

References

-

“Models of Competence in Solving Physics Problems”. Jill H. Larkin, John McDermott, Dorothea P. Simon, and Herbert A. Simon

-

“Thinking, Fast and Slow”. Daniel Kahneman.